I didn't enjoy the collection, and as someone who obsesses about the advent of hostile self-reproducing machines, I was really looking forward to it.One issue I had is that Saberhagen was a chemist and electrical worker by trade but there's not much technical detail on these subjects in his writing. Why not? This is the kind of thing I was hoping for from him.

My biggest complaint is that, for a series of stories about self-reproducing machines, there doesn't seem to be a lot about how machine intelligence or consciousness (if any) is different from us, what it's like to deal with them, the inevitability of civilizations building such machines, or any number of other deeper questions. What he does do, in keeping with one of military science fiction's biggest character flaws, is just re-frame a real historical battle in science fiction terms - in this case, both Midway and Lepanto receive such a treatment. For most people, when they want to read about certain historical battles, they read about them. Yes, Asimov re-told the late antiquity and early medieval period of Europe with Foundation, but there were other lessons to be gleaned (i.e., direct examination of theories of history, types of governments, the predictability of human action over time) but Saberhagen's recasting of these battles, aside from changing costumes, doesn't ask or add anything.

My final complaint is that the machine aliens were nowhere near as alien or remote or sinister as they could have been to be the ultimate life-exterminating protagonists. Daleks are scarier than these things, seriously, although too-human aliens are not unique to this book. Which is my segue to another book, borrowed from friend Greg despite his protestations that I wouldn't like it, Engines of God by Jack McDevitt. (It's bash science fiction day here at Speculative Nonfiction.) McDevitt seems to have set out to create a hybrid hard + anthropological sf, and turns to the trope of "solving" ancient myths by recasting them in modern terms - in this case, the story of Sodom and Gomorrah as an attack by a force which destroys technology-using species. I would say "spoiler alert", but the characters spend the whole book stumbling around ruins trying to figure out if there's any connection between the planets they're excavating, and events on Earth, and any reader not in REM sleep knows that there must be! Kind of like vampire novels where the police find the third victim drained of blood by two puncture wounds in their necks and say "Dangnabbit, this is the third one what ended up like this, what could this mean?"

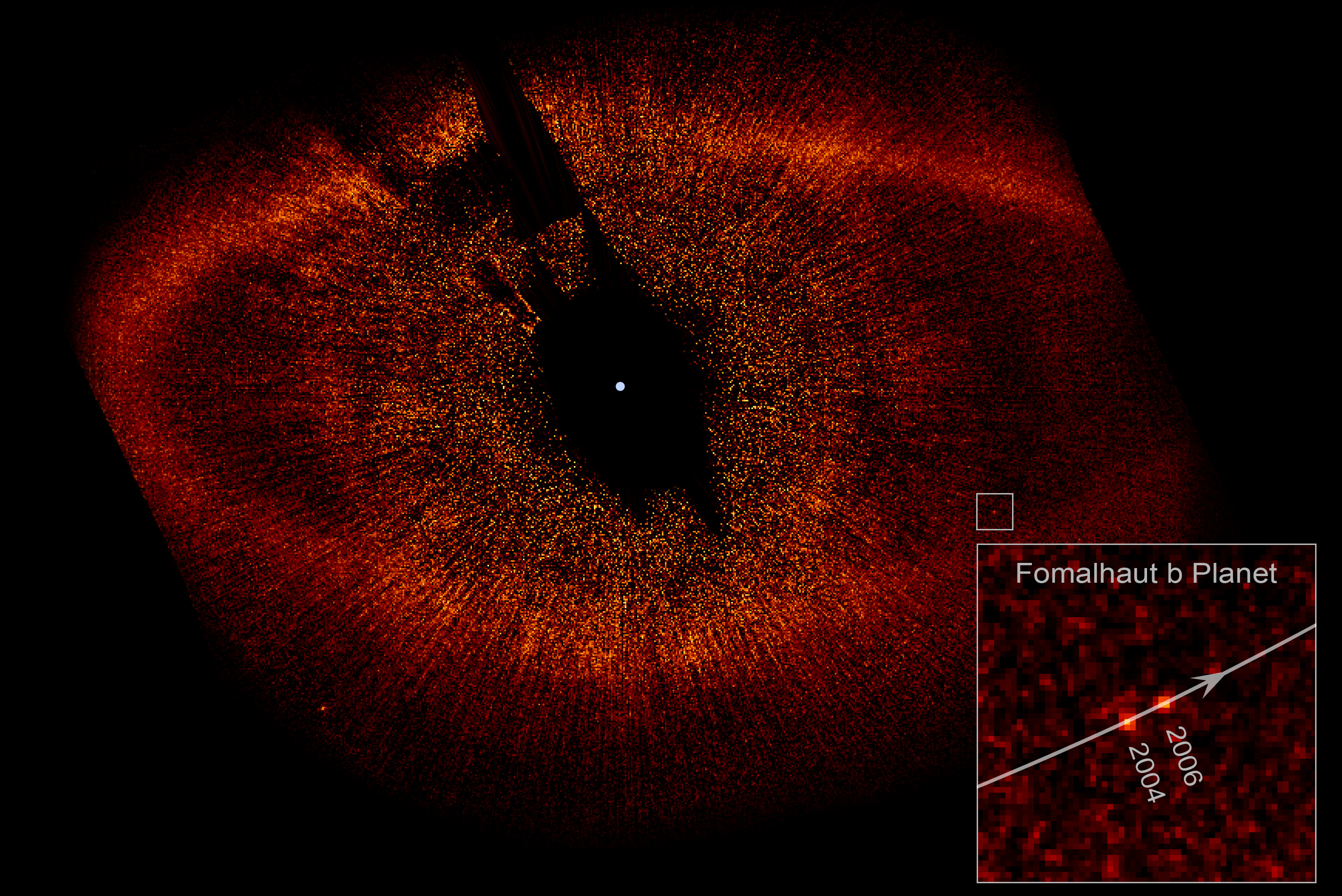

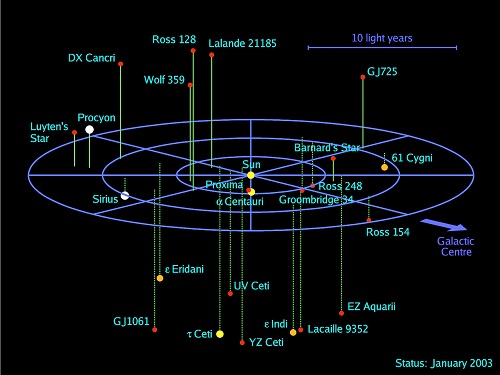

Besides the, again, very human-like aliens (so that anthropological principles apply to them - religion, fertility cults, you name it - I'm not going to spend any more time on that) you have to ask, how is it possible that aliens happened to achieve the same technological level as us within 50,000 years or so, given the much vaster sweeps of time to be had on the scale of the galaxy as a whole? It's hard to be impressed by science fiction where one alien race is considered ancient because they began traveling in space 100,000 years ago - because that's still an amazing coincidence! 100,000 years in terms of the lifespan of the universe is essentially simultaneous with us. "Ancient" would be if they did it before the Earth formed. Even if they did it within 1% of the evolution of life on this planet, that would have been during the late Eocene, when most of the east coast of North America was still a jungle and we were only finally starting to get familiar looking mammals because clear orders had finally emerged (primates, carnivora had at least branched into cats and noncats, etc. Certainly if the aliens that developed space travel within 1% of Earth life's evolution landed, there wouldn't be anyone to talk to.) Even if later in the series it turns out some engineer species had indeed designed all the local intelligences to emerge onto the interstellar scene within a few dozen millennia of each other, that this isn't obviously a coincidence to all the characters right at the beginning makes it very hard to suspend disbelief.

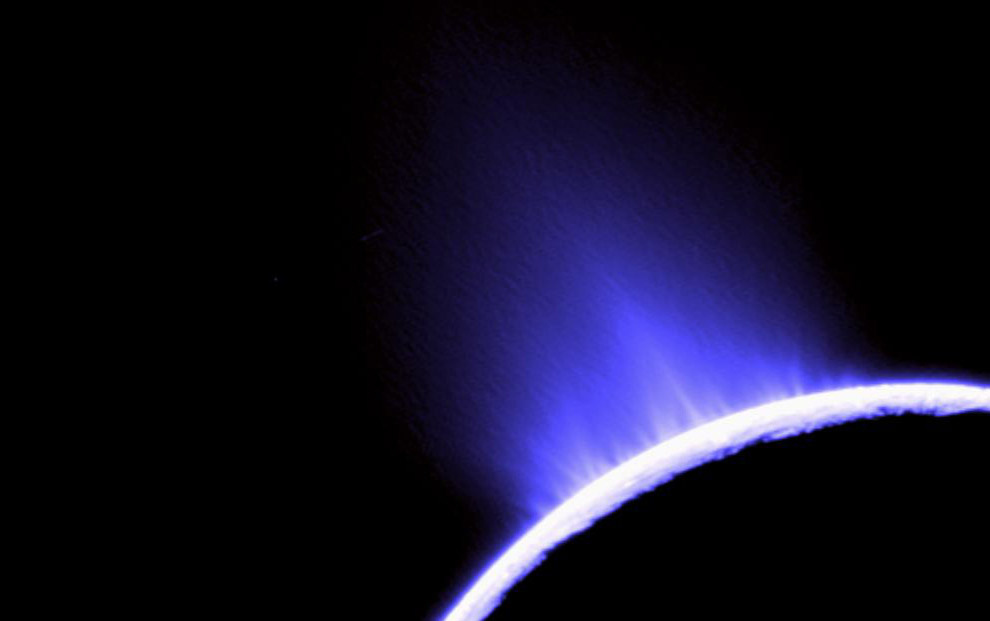

Okay, I'm done beating up science fiction books. That comment about the mammals of the late eocene prompts a question: at what point in Earth's history was a primate the smartest thing on the planet? The ancestral primate was not a brilliant-looking fellow (see below). What were the smartest things before then and during what periods?