Abstract: despite a life of listening to metal (not just thrash and death metal, but

1970s "iron age" metal like Black Sabbath and Deep Purple) somehow I'd avoided Led Zeppelin, beyond what a normal American male my age would get through pop culture osmosis. What finally prompted me to fix this was the curious disconnect I've noticed between the frequent assertions in rock writing that Zeppelin albums had less filler than Black Sabbath, as contrasted against the modern explicit impact of Black Sabbath measured by people today walking around with T-shirts that say "LISTEN TO BLACK SABBATH". Ongoing attention to Led Zeppelin almost five decades later does not approach this intensity of worship. Consequently I set out to binge-listen their full catalog.

Methods: Over a couple weeks, each time I sat down, I listened to at least one full album at a time. While I tried not to explicitly evaluate them as a metal band, my bias of course comes through in

the type of material that moves me. I did not include bonus tracks that were only available on later releases of albums. While I did read about the reception and background of the albums, I did not do this until after I listened to them, to make my listening experience similar to that of people in 70s, who couldn't read the Wikipedia article before the album came out.

Results: from their whole catalog, I dig about a dozen of their songs, especially When the Levee Breaks. Given the number of songs in their entire catalog,

it is therefore inarguable that they have a lot more filler on their formative (first 4-5) albums than Sabbath.

Conclusion: the more direct and congealed-into-riffs appeal of Sabbath may be the reason for Zeppelin's decreased prominence today. And applying the most meaningful criteria - has Zeppelin become a formative influence of my adolescence?* - they have failed. All hail the mighty Sabbath. That said, Zeppelin was making up modern rock as they went, and they were also to some degree a victim of their success, as modern vocalists and the modern guitar solo are often taking their cues from Plant and Page.

*Yes I do expect time travel. Black Sabbath could do it. Their heaviness is such that it pierces time and space.

THE SHORT VERSION

THE SHORT VERSION

Favorite albums: Led Zeppelin, Led Zeppelin IV, and Physical Graffiti.

LZ: Very strong songwriting and guitar work for a debut album.

Favorite songs: Communication Breakdown

LZII: more mellow, down-tempo and bluesier so far than the first one. I would call this blues rock more than proto-metal.

Favorite songs: none stick out

LZIII: Overall III is weaker than I and II. Less memorable, and lead guitar is unpleasantly in the background.

Favorite songs: The Immigrant Song

LZIV: they remembered they were a rock band, and found their distortion pedal and faster tempos again.

Favorite songs:

When the Levee Breaks (my favorite of their entire catalog), Stairway (duh), Misty Mountain Hop, Black Dog

Houses of the Holy: A LOT of the slow-to-mid-tempo songs that rock just doesn't do well, with a minimum of distortion. A slightly better Led Zeppelin III. Were they bored with their formula? Feeling as if they HAD to innovate? Or just thought they can sell more records with this shift? Moments of vocal effects that make the album sound much more modern than '73. Favorite songs: No Quarter, The Ocean

Physical Graffiti: their last strong record. Again they find their distortion pedals.

Favorite songs: Kashmir, In My Time of Dying, In the Light

Presence: my favorite songs are the only two I would ever listen to again. Mostly filler.

Favorite songs: Achilles, Nobody's Fault But Mine

Coda: they sign off with some actual rock, but there are too many 80s-ish moments to really like this record.

Favorite songs: Walter's Walk

FULL REVIEW BELOW.

Metal confession time: until the last few days, probably the only Led Zeppelin song I'd heard all the way through was Stairway. And I'd heard bits and pieces of 4-5 others, frequently from commercials. How did this happen? Unclear. My taste in rock began with Metallica-Slayer-Megadeth, then went back to Maiden, Diamondhead, Sabbath and Deep Purple, and stayed with continuing developments up through 2005 or so (In Flames, Meshuggah, Avenged Sevenfold, Silent Civilian). Zeppelin never appealed, in fact seemed positively thin and boring and didn't smash my face in the way I always wanted music to do. And now that I think back to early 90s high school, it seemed like they drew different kinds of people as fans.

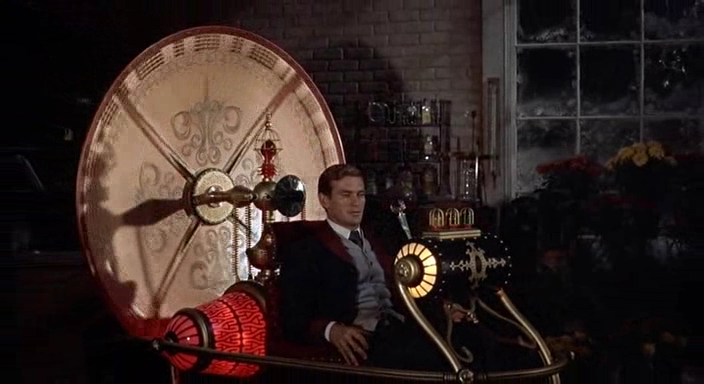

So, after a lifetime of metal, in my early 40s, I listened to their entire catalog in the space of a few days, and immersed myself in the mythos. Yes, that's right. I've watched Spinal Tap, and listened to bands cover their music, and known Zeppelin vaguely through pop culture references, e.g. the pie chart above - I knew there was a lemon-squeezing line and remembered the song that starts with the land of the ice and snow. Sure, I have a passing knowledge, but certainly compared to my experience with Sabbath or even Deep Purple, I really know next to nothing about their catalog. So I sat down to listen to the whole thing. Binge-listening! (Lifelong Zeppelin fans are no doubt horrified by the superficial commoditizing impression that binge-consumption of beloved media invariably invokes, not to mention an uptight middle-aged professional like myself opining on their work after such an experience. Anticipation of which reaction, I have to admit, pleases me greatly.)

But you can relax, because I freely admit that such an exercise is perhaps doomed to disappointment, for

me. This post is kind of

a reverse Chuck Klosterman piece. No matter how transcendent these albums are, at this point they obviously can't define what music should sound like to me the way Paranoid and Justice For All did, and become the formative influence of my adolescence. I can't have the experience of running home from the record store and dropping a needle onto black vinyl and reading the liner notes and arguing with friends about it and imagining how much my out-of-it parents will hate it. But I can still avoid pre-contaminating my impressions, so I tried to only know about each album what you would know before and while listening to it. To maximize the experience I read about the band's history and I knew the year that each album came out, but I intentionally didn't look at the contemporary reactions to each album until after I'd listened to them, to avoid being influenced by them. I also didn't listen to later-released bonus tracks (and none of them seem to have taken the world by storm anyway). My overall reaction is that they certainly blazed some trails, but they're not consistently impressive. Without further ado, here is my detailed reaction to the Zeppelin catalog, by album.

from Ultimate Classic Rock

General Background: reading about their progression from the Yardbirds days to Zeppelin, I get some of the early bio bits from Spinal Tap. More and more when I read about drug-related deaths of musicians, I see how mundanely similar they are. Bonham had alcohol use disorder and choked on vomit, as they often do. (No talk of whether or not it

twas or twasn't his own vomit.) Kurt Cobain had garden-variety opioid use disorder with some signs of personality pathology who escaped from a rehab a few days before - whaddaya know! - he completed suicide...and the list goes on. Randy Rhoads's FWI (as opposed to DWI, which is bad enough) was probably the most interesting from this era in terms of the spectacular stupidity that set it apart from the rest. I also went looking for an online version of

Ars Magica Arteficii by Gerolamo Cardano, from whence comes the ZOSO symbol, but only found the

Ars Magna, which is essentially 8th grade algebra, finally imported into Europe in the late Italian Renaissance from the Islamic world. A guy who's stuck on algebra, and this is the dude that inspires your magic symbol? Not really that spooky guys. (At least do differential equations, there are at least Greek characters in that.)

Led Zeppelin (1969)

Overall the guitar work is more complex than I would expect from a debut album but they'd been in other professional bands before. One online Sabbath vs Zep debate I saw said Zeppelin's records have "less clunkers" and on this record at least, I agree. Zeppelin maybe influenced hard rock more than Sabbath, although Sabbath more directly hit the nerve and that's what generates the obsession in metal. (Better to be loved by few...)

Babe I'm Gonna Leave You is good.

Dazed and Confused is familiar.

Communication Breakdown is a classic and I'd heard the riff before. Later on Zeppelin moved away from building songs in the modular style familiar from later metal, which you can view as a positive or not. (My vote: not. I live for good riffs.) I've heard Metallica cover

How Many More Times and not known where it was from. There were moments throughout the album where the drum sound reminded me of the parts of Kashmir I'd heard before. Reflecting on Plant's personal and vocal style, he's an early David Lee Roth. He can project but it's his confidence in his delivery that lets him do what he does.

Led Zeppelin II (1969)

Early in the record, more mellow, down-tempo and bluesier so far than the first one. I would call this blues rock more than proto-metal.

The Lemon Song - ah, there's the line about the lemon. And that exposes the rift between hard rock and metal and why Zeppelin is more of an influence to the former: sexuality as a theme (or at least "normal", non-threatening, non-taboo sexuality. Pantera can sing This Love because it's scary, but there's always an overtone of moral judgment. Not many metal bands that use pathological sexuality seem to want you to think that they actually

do it, or approve of it.) One study showed that

metal and classical fans have a personality makeup similar to each other, and different than people who like other genres of music. Classical and modern metal are in some sense more abstract, absent personalities in the performance, more often instrumental. Maybe that's what draws the different sorts of people. Hard rock (today, basically a dead genre) owes more to Zeppelin than metal does. Still, can you imagine Tom Araya talking about his sex life?

As for the songs,

Heartbreaker's intro riff is solid.

Living Loving Maid is also familiar. That's more the tempo I'm looking for from a band claimed as

the, or at least a major, progenitor of metal. (Yes, there are slow tempo metal bands. They're not doing the same thing mood-wise that Zep is doing in their slow songs.)

Ramble On is the best of the three hobbit-themed songs they've written, partly because Robert Plant is actually saying phrases that approach poetry. The song reminds me of the best moments of Credence.

Led Zeppelin III (1970)

The Immigrant Song: there are those Vikings. Now that I hear it I may have listened to this one all the way through. Zeppelin really did not have a good crunch (my own personal taste? that's the objective reality of where metal went.) Sabbath's Paranoid came out within a month of this and had a better crunch. I couldn't wait for

Friends to be over. It kind of meanders. It sounds like a studio jam that should've been cut. Overall III is weaker than I and II. Less memorable, and lead guitar is unpleasantly in the background. Going back to read about it, it got deservingly bad reviews.

Out on the Tiles has that low crashing punctuated motif, but the guitar just isn't strong enough to bring it off, and the riffs are weak. Slide guitar in

Tangerine is a brave choice, but overall doesn't rescue the song (apparently about his 1960s girlfriend from Kentucky).

That's the Way was worse than having a cavity filled. As much as Zeppelin anticipated hard rock, their accoustic bits and half-assed ballads frankly suck. 80s power ballads do what they're trying to do much better than the soft ones here, i.e., it pains me to say I would prefer Bon Jovi to anything, but this song pained me more than enough to say it.

Bron-Y-Aur Stomp is also a different move but at least it has energy. It seems like by this album they were already getting bored with writing rock songs. Bands don't usually move into their "mannerist" periods so quickly (often characterized by ethnic overtones; Metallica's country style on Load, Sepultura's Latin percussion, and here Celtic flavor from their lair in Wales.)

Led Zeppelin IV (1971)

A dramatic improvement over its predecessor.

Black Dog is another classic. This is Zeppelin's answer to War Pigs. Given the strength of the riff, the addition of major third harmony later in the song, and the driving tempo, this is arguably proto-metal. There is an interesting rhythm change during the key change in the main riff. When

Rock and Roll started, I thought good, Zep is back (to playing rock) as opposed to the inchoate ballads on III. Amazing how prominent Bonham's drums are, to good effect too. Unfortunately, the record loses momentum because the Battle of Evermore is a repetitive waste of time, Middle-Earth-themed or not.

And THEN

Stairway, the ancestral power-ballad. Their other amorphous slow numbers can almost be forgiven. I skipped this because I already know it. I'd heard parts of

Misty Mountain Hop before but didn't know it was Tolkien-inspired. The verse has that strange chromatic triplet pattern. Come to think of it, Zeppelin does anticipate this aspect of metal (weird scales) better than Sabbath, whose jarringness is mostly from low register and diminished fifths.

Going to Califoria is annoying, because Robert Plant is annoying when he's trying to sing about sensitivity and introspection. I'd heard parts of

When the Levee Breaks before, and it always reminds me of Scarecrow on Ministry's NWO. This song is in "creepy" territory, rare for Zeppelin. This is definitely my favorite song on this album, and maybe now, of Zeppelin's entire catalog.

from lawyerdrummer.com. Did you know Zep just won a big

plagiarism suit a few weeks ago? About Stairway to Heaven

being a rip-off of Taurus, by Spirit

Houses of the Holy (1973)

As a whole, this album has its moments but Led Zeppelin IV it ain't. It has a LOT of the slow-to-mid-tempo songs that rock just doesn't do well, with a minimum of distortion. This is a slightly better Led Zeppelin III. Were they bored with their formula? Feeling as if they HAD to innovate? Or just thought they can sell more records with this shift? (If so, it worked.) There are moments of vocal effects that make the album sound much more modern than '73; despite this, by this point I'm getting sick of Robert Plant. He's not a bad singer but he's no Chris Cornell; he's also not selling his personality as much as David Lee Roth. Of course they're both influenced by him, and specializing in aspects of his performance (is it fair to compare an archaeopteryx with an eagle and an ostrich?) so in that way Zep and Plant are victims of their own success.

Onto the songs: It quite escapes me why so many people claim to like

The Song Remains the Same. Until now my only contact with it was a lyrical reference in a Carcass song, and had the situation remained this way my life would have been better for it. At moments it reminds me of Rush's

Villa Strangiato but less imaginative.

Rain Song does establish a nice "rainy mood", but I was worried that this one would go nowhere, and it kind of doesn't until the drums and strings start later in the song. The recording of Bonham's drums often sticks out and this song is no exception (might actually be the most interesting thing here.) In

Over the Hills and Far Away, the verse's vocal melody is quickly recognizeable but there's really not much else to this song. Lots of heavily bent notes imparting an almost country style here (not just in this song, throughout the album).

The Crunge - I will never get this 3m15s of my life back. Reminds me of Jane's Addiction, who I also don't care for. (Clearly, every time I think they sound like a later rock band, you can make an argument for influence. But this song still sucks, and so does Jane's Addiction.) The trance-inducing riff in

Dancing Days is immediately recognizeable. Somehow this doesn't get old, although certain elements of the song bother me when they're outside country or Southern rock (is that slide guitar again? I didn't like it when Kirk Hammett started doing it on the Loads either.)

D'yer Mak'er is not a rock song, but it's very unique. I don't know how I'd even describe the main riff. I still like it. Where I'm critical of the incoherent, un-memorable attempts at originality elsewhere on this album, this song feels like an actual song. A darker-sounding song,

No Quarter is the "When the Levee Breaks" of this album, that has a steady development and some sustained discord and unhurried but solid riffing. I like this one a lot; maybe my favorite on the album. The main riff of

The Ocean is instantly recognizable. The bizarre rhythmic pattern of it keeps it interesting and the little a capella section in the middle is nice.

Physical Graffiti (1975)

Better than Houses of the Holy. At this point, every second album is solid, and the others are weak, much like Star Trek movies. But Physical Graffiti has a lot of cuts leftover from LZIII and LZIV; I was not surprised on learning this. Physical Graffiti is also the first record on the Swansong label, and the quality drops after this one. Because they're now more isolated from sales concerns? I know this is anathema to suggest in art and especially in rock, but come on, incentives matter to human beings. (There's an analaogous drop in the quality of output from scientists who win the Nobel.) In

Custard Pie I'm happy to hear that they found their distortion pedal again and it feels a little more drum-driven; otherwise not blown away.

In

The Rover I don't mind the bent notes because again, it grooves, and the drums are driving. Apparently there's a phase effect added to the guitar but I can't hear it.

In My Time of Dying is an unambiguously good song. The quiet intro is nice, and maybe I like it because the main riff reminds me of Danzig's Twist of Cain. And there's a fast section in the middle with some solid lead work. Looking at the Wiki article, a lot of similarities in the recording to another favorite of mine When the Levee Breaks. Lyrics are the usual bluesy last minute prayers to the Lord, which normally I'm partial to, but "Oh, Gabriel, let me blow your horn", I mean come on Robert.

Onto the songs -

Houses of the Holy - interesting that this is here and not on the previous album. The hummable melody and cleaner (but still more prominent) vocals immediately suggest a deliberately radio-friendly song. For no fault of its own,

Trampled Under Foot reminds me of other songs that I can't name, that I keep expecting it to shift into. Of course it does not which gives it an uncomfortable itch. (Green Day songs have a habit of seeming familiar the first time you hear them too.) Another problem with this song: the main riff has an unfortunate Zep pattern of busy then stop (open few seconds with bass/drums) busy then stop (open few seconds...) that I find very disjointed, not in a deliberate Meshuggah way either, but rather like it can't decide whether it wants to be a rock march or groove.

As for

Kashmir - I've heard large parts of this one before and always liked it. See,

this is a good song. This song is a rock march and knows it. The well-placed exotic scales and brass parts somehow don't seem to stick out. I had heard previously that Bonham played out in the hallway to get the right drum sound for this song, and they do sound more distant (perfect for the song), but this may be why I find myself always listening to the drums in many of their songs. You can hear the phase effect (most overt right at the end). I'd also never counted to figure out what's going on with the meter but it sounds like it's basically in 3 (unambiguously for guitar, kind of cheating on drums by making it 4+2 so they line up in multiples of 6). Reading about the composition, I'm not surprised that they took their time composing it; this is clear in the way it's so full of well-developed ideas.

The keyboards at the start of

In the Light had me a bit worried (a little too 70s "look we have a Moog!") but then there's that main riff that starts at 3 minutes and is

outstanding. (This is the first time in the whole catalog that I wanted to go get my guitar and learn it.) I like

Bron-Yr-Aur and the metal strings, but for some reason when there's an (apparently) accidentally muted note on an acoustic piece like this it really bugs me because it sounds sloppy. Maybe that's what Page was going for but for me, it mars an otherwise nice clean relaxing interlude. ("But that makes it sound more 'live'!" you object. Yes! Correct! And you're not in your mom's garage anymore! Do it over!) In

Down by the Seaside, the flange and the slide guitar are too much, and the melody and echo make me think I'm listening to Dolly Parton or something. And then at 2m12s, Dolly is replaced by...a mess. ++Ungood. The ending of

Ten Years Gone feels like a power ballad that never quite takes off. Unsatisfying.

Night Flight starts with Plant right away which can't be a good sign. The best thing I could say for this one is "filler". Mostly written by John Paul Jones. Sorry bro.

The Wanton Song is a classic busy-open-busy Zep riff but I like it. I quite like this song. I think the internal structure of the riff makes the whole phrase feel more organized. Often you'll hear rock bands picking strange chords to try to be original and think it's a phenomenon of modern rock looking for something new, but strange chord choices are found throughout Zeppelin's work (here in the chorus) so if today it's done out of boredom and a desperate search for originality, well, it was already happening in the early 70s.

Boogie With Stu - alright, this one doesn't sound like rock but I have to admit it's fun. But the loud echoed vocals damage the old-timey mood. By the time I get to

Black Country Woman, I'm too tired of hearing about Robert Plant getting laid to pay attention. Leaving the little spoken moments in at the beginning and end of the song create some intimacy that was probably much more rare when this was released. (Think of the rattling of the snare in response to the guitar on Metallica's St. Anger; a rough edge rare for them.)

Sick Again - Okay, even if this is another one about Robert Plant getting laid, at least there's pity and shame involved. Some good lines in this one. Lyrically, maybe my favorite song in the catalog.

Presence (1976)

Presence (1976)

This record has only two songs I would ever listen to again, and one of them was a cover of an old blues man. There were bonus tracks released later but I wanted the experience of the original record so I didn't listen to them until after I was done with whole project. If that kid on the right side of the album cover was 10 when it was released, he's 50 today (although the baby from the Nevermind cover still makes me feel older).

Achilles Last Stand immediately takes off with a not terribly distorted but relatively heavy galloping riff. The guitar melodies between the riffs are the best part of the song. The dramatic martial snare stop-rhythm during the guitar solo is nice. The classic theme doesn't hurt but as always it seems to be Plant complaining about women, now embellished with a reference to Atlas. This one wouldn't be so close to ruined by Plant's singing if there weren't such a prominent echo; cleaner recording would have helped.

For Your Life has big open sections that disrupt the rhythm and don't work here, and the slide doesn't keep it interesting. The descending riff that makes its first appearance around 2:30 isn't bad, but this song has the modular riff-based feel of later metal without the quality in the riffs to sustain it. And, yes it's my bias in favor of an extremely distorted solid state guitar sound (think Pantera or Obituary) but I just can't take the half-assed twangy distortion of the riffs outside the solos. (The solo here isn't bad, for what it's worth.) Judging by the fact that

Royal Orleans just ended as I was typing the last sentence and nothing caught my attention, forgettable.

Nobody's Fault But Mine opens with a nice guitar and hummed vocal melody, a good strong bluesy pentatonic riff that then adds harmonica. #2 favorite on the record after Achilles. Only later did I see that it was adapted from an old Delta blues song. I would've believed it for a Zeppelin original but this origin explains its strength (both a compliment to Delta Blues, and not a compliment to late-era Zeppelin.)

Various aspects of

Candy Store Rock make it seem as if they are doing a half-assed Elvis impression. Reading later, they did indeed intend it as a rockabilly tribute and took an hour to write it (and as Michelangelo said of the hackish and deadline-driven paintings of Georgio Vasari, "one can tell".) It was released as a single and did not chart in the US, which is a credit to the tastes of the American rock-consuming public in 1976. Regarding

Hots On For Nowhere, is this pop? What is this? What are they even trying to do? Overall a mess.

Tea for One has a promising opening. Strange riff and grooving rhythm that work well together. Out of nowhere it slows down and the slow blues section is nice but the lead work at times feels crowbarred in, and the whole thing could be about three minutes shorter. Seems like the equivalent of Sabbath's Faeries Wear Boots.

Above: from Wikimedia. Meanwhile, Ozzy was at the Correspondents Dinner already in like 2002. Below: the older Robert Plant always reminded me of Sark from the original Tron. Yeah I have weird associations with people, so sue me.

In Through the Out Door (1979)

Review in a nutshell: Why couldn't Bonham have died before they recorded this? (Really.) It's not surprising at all to read that both Page and Bonham were in the depths of substance problems at this time, and to read interviews with Page justifying this album out of the side of his mouth, he doesn't say much about that (frequently an addict has poor insight into the disease's effect on them.) As for the record itself: that endlessly repeating slow-paced jangling guitar riff in

In the Evening makes me want to die, and not in a good way. Is

South Bound Suarez a Billy Joel song rescued (without reason) from the cutting room floor and covered by Zeppelin? The impending approach of the 80s is strong in this one. Not surprisingly,

Suarez is one of the few Zep songs not to be at least partly written by Page (i.e. Zep's McCartney) who was apparently doing more heroin at that point than Kurt Cobain on payday. Goddamn but Page's "lead" is sloppy in this song.

I've definitely heard

Fool in Rain before and I'm shocked that it's Zeppelin. You could make an argument that a lot of these songs I don't like are just their less rock-ish versions and show Zeppelin's range...yeah, their range of suckitude! This one is more like Paul Simon or something. As of this song I'm starting to think this record is Zeppelin's version of Rush's

Hold Your Fire. As regards

Hot Dog: once in Durango my wife and I had dinner at an old Western-themed bar with an old-timey piano player. That was enjoyable. The best thing I can say about this song is it reminds me of that dinner. Wow, to make

Carouselambra they bought a keyboard! Sounds like the song my friend Matt wrote in junior high. Or maybe something for the credits of a 1970s Doctor Who episode (you know when they had like 200 pounds Sterling for each episode).

All of My Love is the only recognizable one on the record. The keyboard solo is maybe my favorite moment on this tumor of an album, maybe just because anything is better than Page's messy guitar work here. A slightly better

In the Evening but Plant's vocal weakness is shining through. As for the last song,

I'm Gonna Crawl, yeah to a bridge and jump off if I have to ever listen to this song again.

Above: Come to think of it, Plant looks like St. Vitus too.

Above: Come to think of it, Plant looks like St. Vitus too.

But not like Thomas Sydenham, who looks a little bit

like John Paul Jones if he kept his hair long

(neuropsychiatry in-jokes, hahaha!)

Besides St. Vitus Dance is a Sabbath song.

Coda (1982): definitely has song strong moments, because they again remember they're a rock band, but there are some soft spots and "welcome to the 80s" moments too.

We're Gonna Groove has some strong bits (strong, as in coordinated punchy guitar and drums) but no part or riff from this song stands out.

Poor Tom is poorly organized and otherwise sounds like another of their whatever-it's-called Bryn-Mawr Welsh bits (checked: yes, recorded during their "Welsh period").

I Can't Quit You Baby is a nice bluesy piece with a lot of hyperactive soloing, which fits poorly and would normally piss me off but here I enjoy it (and of course, turns out it's an Otis Rush piece).

Walter's Walk begins with a promising tempo and has a nice little rising tail of a riff first heard at 1m45s, and then really takes off at 3m25s. Finally!

Ozone Baby again sounds very early 80s in a bad way, and while the modular more riff-oriented design of songs on this album is also heard in this song, the riffs

aren't good. On the next song

Darlene, clearly as a joke someone snuck an REO Speedwagon song into this playlist. Which is sad, because it opens with a pretty cool riff and has not terrible soloing!

Bonzo's Montreaux starts as an all-percussion piece, a nice surprise that I wasn't expecting; not sure what the other instruments are, and I have to hand it to Page, his early interest in electronics (for a rock guitarist) enhances this piece.

Wearing and Tearing is fast, which about the best thing I can say for it, and was apparently intended to compete with punk bands. I find it a sad end that the last song on a real Zeppelin album was a (not good) attempt to compete with punk, although I like the way Bonham's drums are the last sound to fade out.

Above: Come to think of it, Plant looks like St. Vitus too.

Above: Come to think of it, Plant looks like St. Vitus too.